Zellij - often referred to as Zellige or Zelige - is a moorish art form that is heavily featured in Moroccan architecture. We have long since had an incredibly deep appreciation and affection for zellige and its imperfect charm - but especially so after our trip to Marrakech a few years ago with our dear friends, Holly Phillips of The English Room, Julia Buckingham of Modernique Inc. and Cathy Austin of Catherine M. Austin Interior Design. We digress for a second, but that’s us…. riding CAMELS in the Atlas Mountains!! It truly was the trip of a lifetime, y’all! To see more, check out the hashtag we used on the trip and for the Instagram Takeover we did for Traditional Home.

Provenance: Ormolu

There is something absolutely magical about the discovery of an antique piece with an elaborate history. The story of Ormolu, a method of gilding that dates back to the 18th and 19th centuries, helps uncover the rich narrative of beloved furnishings and objects of art. Derived from “or”, french for “gold”, and “molu”, french for “ground”, the Ormolu technique is also sometimes referred to by the French as Bronze Doré.

Provenance: Lotus Flower

We often find ourselves drawn to certain shapes, forms, or motifs from nature for no apparent reason other than it literally calls to us. As art imitates life, the lotus flower, ripe with the symbolism of purity, enlightenment, self-regeneration, and rebirth, has found its way into creative expression in all manner of ways and it is one of our favorites.

Provenance: Flame Stitch

Flame stitch - that bold, often colorful, zig zag pattern - is hot. Think of flame stitch as a design rather than needlework, especially when considering how it is used today. While flame stitch is trendy now, it has been around forever, probably since the 13th century. Let’s take a quick look at flame stitch’s history.

The origin of flame stitch is murky and romantic. Most scholars agree that it is primarily Italian, with either a dash of Hungarian or Middle Eastern roots thrown in. Flame stitch could be a hybrid of two stitches, the brick stitch and the Hungarian stitch (seen in the 13th century German altar curtain below) brought to Italy by a beloved Bohemian princess on her many trips there. Alternatively, flame stitch may have a Middle Eastern relative, given its resemblance to ikat, that traveled to Italy via the Silk Road.

While we can’t DNA flame stitch, one of the earliest surviving examples is found in England. There, in the Elizabethan manor, Parham House, an entire room is still upholstered in Italian wool from the 16th century bearing a flame stitch pattern. The principal bed at Parham House also is adorned with flame stitch. Surely it is not coincidental that Mary, Queen of Scots (who ruled Scotland then) was Marie de Medici’s sister-in-law.

Italy has few extant early examples of flame stitch. Some 17th century chairs wearing the pattern reside in the Bargello Museum in Florence, explaining why flame stitch is sometimes called “Bargello” or “Florentine” stitch. The French call the pattern “Bergamo”.

Flame stitch remained popular in the 18th century spreading throughout Europe and to the colonies. It often decorated clothing then, as these British shoes and American pocketbook from that time period show. It truly must have been all the rage, as the ladies of the Greenwood-Lee family thought it chic enough to include in their c. 1747 family portrait.

Flame stitch never really went out of style. The Scalamandre flame stitch velvet covering these 19th century settees is period perfect.

New fabrics are still being created today. Have a look at these textiles from Schumacher and Zimmer + Rhode, and how designer Nina Farmer upholstered a chaise in flame stitch for her Boston townhouse.

In the 1970s, flame stitch wallpaper was all sorts of groovy. Meg Braff recently updated that old seventies look with a new wallpaper dubbed appropriately, “Flambe.”

The flame stitch pattern (and its appeal) hasn’t changed much over the years. With maximalism now in vogue, we wouldn’t be surprised to see a fully upholstered flame stitch room someday soon.

Flame stitch. Still on fire.

This post was guest edited for CLOTH & KIND by Lynn Byrne. lynn is an expert in decorative arts and design history, who also has written extensively about art, travel, and interior design. She studied decorative arts at Parsons and is well-known for explaining design terms and themes found throughout history.

PHOTO CREDITS // German altar curtain from Bayrose, ikat example from Hand Eye magazine. Parham House photos by Andreas von Einsiedel for Homes & Antiques magazine. British shoes from Metropolitan Museum of Art. Pocketbook from Museum of Fine Arts. Family portrait from the Museum of Fine Arts. Nina Farmer’s home, by Paul Raeside.

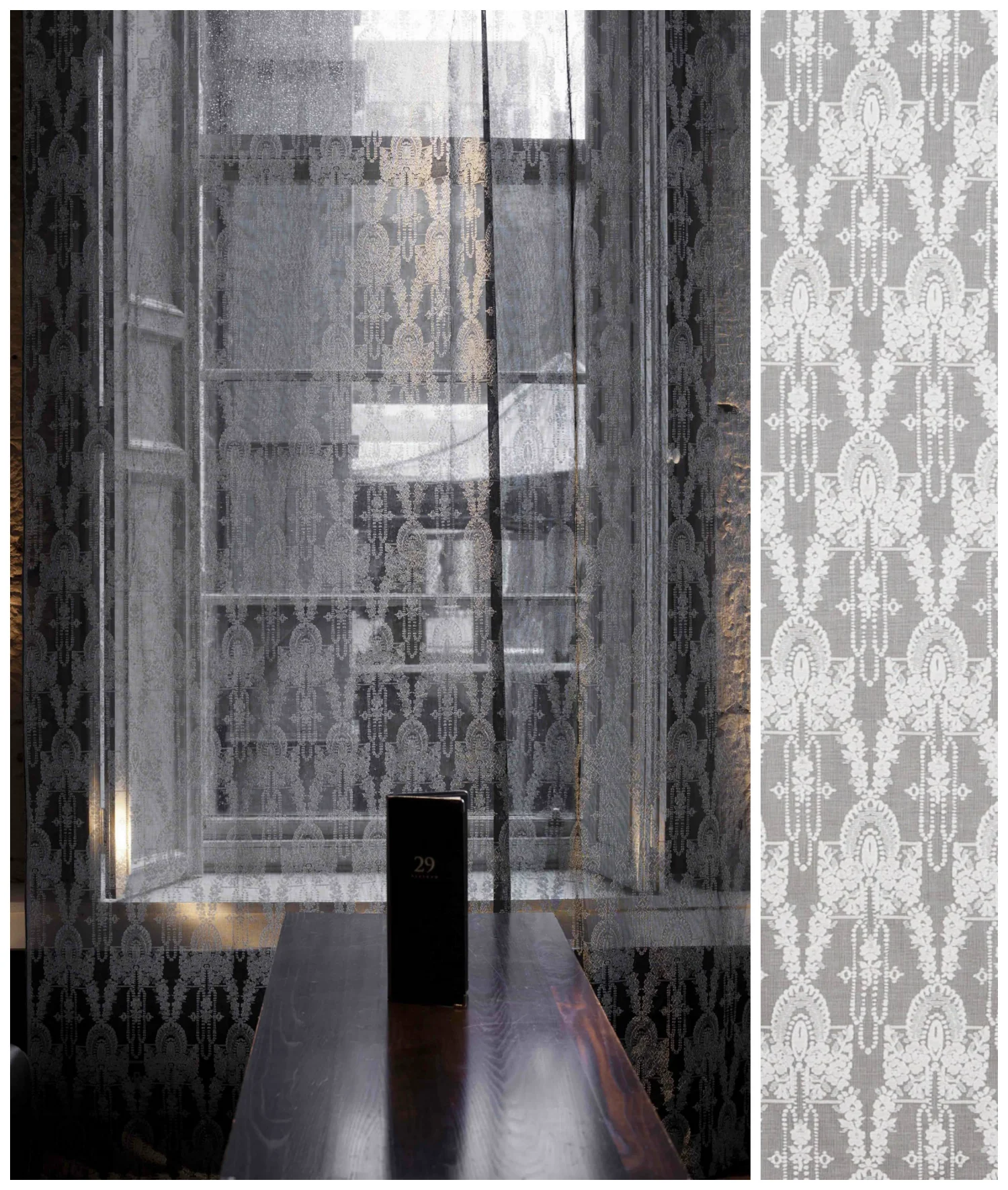

Provenance: Nottingham Lace and Madras

Who hasn't been seduced by the image of lace, moving softly in the breeze, with the sun streaming through leaving an intriguing pattern on the floor. Or perhaps a tuft of lace at the neckline of a beautiful woman. So romantic. Kind of feels a bit like Downton Abbey or a Ralph Lauren ad, don't you think?

Well, as it turns out, there is only one remaining mill in the world that continues to make true Nottingham lace (and its cousin, madras) - and it is, natch, the lace that you see on Downton Abbey and couture fashion from brands like Ralph Lauren, and Scottish designer Elizabeth Martin whose designs are shown above.

Who is keeping this legacy alive? The firm Morton, Young and Borland Textiles, based in Ayrshire, Scotland about 25 miles from Glasgow.

And what's so unique about MYB Textiles' lace? Two things, and both are irreplaceable. First it is the looms that their product is woven on. Nottingham refers to the place where the machine and technology for making the lace first developed, not the lace itself, and MYB Textiles' looms are over 100 years old. No other firm has them.

MYB has carefully maintained their original looms from the company's inception in the early 1900s and acquired additional ones as other companies have gone out of business. These special looms allow MYB Textiles to create wide width fabrics, with highly ornate patterns or, if need be, simple gauze-like textiles.

But don't assume that MYB Textiles is lodged firmly in the past. Rather it is the firm's unique ability to adopt modern technology while respecting it's heritage that has allowed the company to survive and thrive.

And that brings us to MYB Textiles' second unique feature. Unlike other companies that produced these textiles, MYB has installed a carefully orchestrated apprenticeship program to allow skills to be passed down from generation to generation. Plus, a look at the company's Tumblr account also reveals that they regularly take interns from Britain's designs schools, opening themselves up to fresh new ideas from young designers.

An example of MYB Textiles' ability to marry old and new goes to the heart of their business. They have a vast archive of historic designs that they often draw upon for inspiration. Yet, those designs are now developed with computer assistance. The company has found a way to harness it's 100 year old looms with electronic jacquards allowing the use of CAD.

Margo Graham, one of just two Nottingham lace designers still in existence (her one-time apprentice, Kashka Lennon is the other) explains, "Designing used to be watercolors on draft paper (seen below, left) but now it's computer-aided. The techniques are still the same but all the skills have been transferred. All the cutting and pasting had to be done by hand in the past, now it's a lot easier."

Even with the advent of modern technology, however, there is still much done by hand. Those 100 year old looms are quirky. They run slowly and require careful monitoring.

Once the fabric is loomed, it is taken straight to the darning room to be checked for imperfections. A hand darner will "invisibly" correct any error, be it by adding missed stitches to the pattern or by removing an extra stitch, known as seeding. Not surprisingly, it takes many years to become a good hand darner.

So what's the difference between madras and lace? With madras, below left, the pattern is woven onto a gauze background, so that only the pattern, not the ground, needs to be designed. Lace (below right), on the other hand, requires that both the background and the pattern be designed.

Modern technology or not, its obvious that the lace and madras produced MYB Textiles are imbued with romance from the outset.

EDITOR CREDIT // This post was developed and written by guest editor Lynn Byrne.

IMAGE CREDITS // All lace shown is produced by Morton, Young and Borland Textiles. Quote from Margo Graham taken from an article published in Homes and Antiques magazine in November 2014. Fashion designed by Elizabeth Martin and fashion photos came from Textiles Scotland. All other images from the MYB Textiles website.

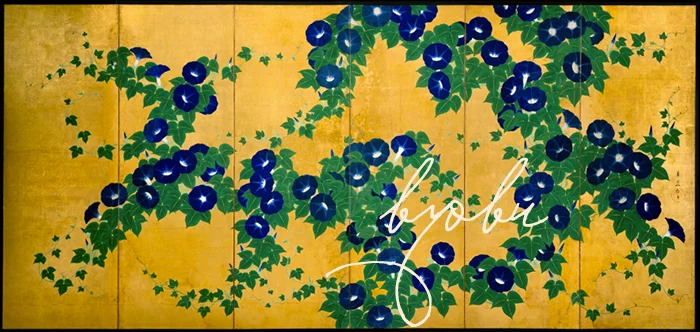

Provenance: Byobu

prov-e-nance \ˈpräv-nən(t)s, ˈprä-və-ˌnän(t)s\noun. the place of origin or earliest known history of something.

Guest edited by Jacqueline Wein, Tokyo Jinja

Perhaps the very essence of Japan can be found in the hand painted screens, called byobu, which have flourished as an art form in Japan since the 8th century. Byobu literally means “wind wall” which gives a clear sense of their original purpose – to block drafts. Over time, their mobility and flexibility allowed them to be used almost anywhere, to block unsightly objects or repurpose a room, as well as serving as beautiful backdrops for tea ceremony, ikebana and visiting dignitaries. Ornate screens and those using gold and silver leaf helped proclaim the status of their owner. Like much of Japanese artwork, screens originated in China but were slowly but surely domesticated and changed in Japan, with a high point being the introduction of paper hinges, allowing the artist a single large canvas to create an image, rather than completely divided panels.

I considered writing on other subjects this month, but with my imminent departure from Tokyo, I realized that I had to cover something very near and dear to my heart. Add to that my discovery, at a big antiques fair earlier this month, a divine silver leaf byobu painted with naturalistic pine in the richest of greens and my topic was set.

Of course this beauty came home with me where I cannot stop admiring the finesse of the painter who implied mountains in the background with the merest hint of line. The silver leaf literally seems to glow as if lit from within.

The period between the late 16th to the 17th century is considered the "golden age" of byobu painting, with daimyo and samurai leaders commissioning works of art on a large-scale, designed to decorate their castles and awe their constituents with their wealth and power. Screens from this period often continue to reflect a bold Chinese heritage and make free use of bold brushstrokes and Zen themes.

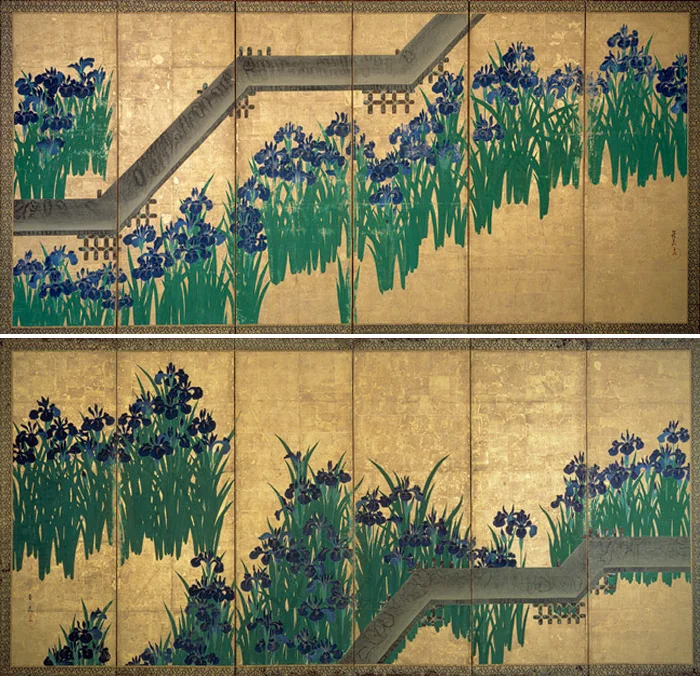

Prosperity under the Tokugawa shogunate from the early 17th century through the mid-19th century, encouraged painters of various schools to create screens in many different styles – not just for the samurai and aristocratic elites, but for wealthy farmers, artisans and merchants. The Kano school is perhaps the most well-known, being the dominant school style for nearly 400 years. The Kano family itself produced many great artists and many students of the school went on to take the Kano name. The Rinpa school, created in 17th century Kyoto, is one of the other most famous schools, known particularly for the work of brothers Ogata Korin and Ogata Kenzan. I have written about the Ogata Korin iris masterpieces before, and they continue to be some of my favorites.

Other schools include the Tosa school, whose subject matter and techniques derived from ancient Japanese art, as opposed to schools influenced by Chinese art, notably the Kano school. However, by the late 17th century divisions between schools had become less marked as the artists willingness to experiment broadened.

As the breadth of topics widened, so too did screen commissioning and ownership. Most common were pairs of full height 6 panel screens, but other shapes and sizes proliferated with specific names and uses. Topics such as the four seasons, flower studies and detailed works featuring the Tale of Genji and other stories were popular. I particularly enjoy some of the more casual screens showing everyday life - like this pair of tagasode screens - meaning "Whose Sleeves?" a common theme depicting beautiful kimonosdraped across a wooden rack. Generally unsigned, tagasode screens are thought to have been painted by local artists whose ready-made works were sold to buyers off the street, rather than being commissioned.

Today, screens are more likely to be hung on the wall rather than stood on the floor. They lose some of their visual movement that way, but it also enhances the viewers ability to encompass the painting directly. I love the parallel between the silver leaf grids in the screen and the Bennison fabric pattern in this room by Windsor Smith.

Finely detailed story screens like this 17th century byobu depicting the Genki Heike Battle between the Minamoto clan and the Taira clan may have had their heyday in that century, but feel just as relevant today when mixed with an antique Spanish refractory table and patchwork boro in Amy Katoh's riverfront home.

Their detail or simplicity, their ever-changing response to light, their functionality and portability and their ability to work in any style decor, make byobu any decorator's best friend. For more images and information about these Japanese beauties, you can visit my blog Tokyo Jinja and my Byobu Board on Pinterest.

Have you used byobu in your home or a client project? We'd love to hear about it.

IMAGE CREDITS | All byobu screens via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, other credits as noted and linked to in the post above.

Provenance: Toran

prov-e-nance \ˈpräv-nən(t)s, ˈprä-və-ˌnän(t)s\noun. the place of origin or earliest known history of something.

Guest edited by Jacqueline Wein, Tokyo Jinja IMAGE | Antique Toran via The Textile Museum of Canada

A number of years ago I spied a charming doorway textile at the home of a dear friend. Clearly Indian in origin, it was a rectangular banner with small fabric flaps hanging down and tiny mirrors embedded in the pattern. She told me it was a toran, a hand embroidered and embellished door hanging, traditionally made in Gujarat, on the coast of Northwestern India. My fascination with them grew and over the years I have continued to keep an eye out for them.

The word toran (or torana) itself originally referred to sacred gateways in Indian architecture, with roots in Buddhism and Hinduism, like this pair of 12th century sandstone ones in Vadnagar, Gujarat. It is easy to see the connection between the embroidery of the fabric hangings and the detailed stone carvings, as well as in their function to welcome both the gods and people. Decorative toran also play a role in holidays like Diwali and Holi or at weddings and celebrations as they are believed to be auspicious and lucky. The doorway blesses every person that walks under it, showering them with an abundance of love, prosperity, health and happiness. While the heavily embroidered ones tend to be regional to Gujarat, toran in other forms are popular throughout India. In the south, green mango tree leaves are threaded together and hung across the door. In Northern India, marigold flowers are strung together and used the same way. The small flaps that hang from the fabric versions are meant to represent dangling leaves and flowers.

IMAGES | Torana Arch via Vadnagar, An Ancient City & Marigold Garland via Mitai and Marigolds

Often times toran are used in spaces other than actual doors to represent a passageway. This welcoming example from Sibella Court's Nomad book beckons one to enter and cozy up for a restful nap.

IMAGE | via Nomad: A Global Approach to Interior Style by Sibella Court

The Kutch region of Gujarat is particularly well known for its embroidery techniques, with specific tribes and communities having their own particular style. Shisha, which is the Indian word for little glass or mirror, is the most distinctive technique in which small mirrors decorate the textile, being held in place by a framework of overlaid embroidery stitches. No glue is used and the mirror is not threaded through or attached in any other way. It was believed that the mirrors had the power to ward off evil spirits by trapping or confusing the evil eye. While many of the other decorative stitches, such as the chain stitch, are universal, shisha work is unique to the Indian subcontinent. It comes as no surprise to me that women are solely responsible for these creations and that motif and patterns are not copied or written down, but instead passed along orally.

IMAGE | Antique Kutch Embroidery Toran from NovaHaat.com

Base fabrics and threadwork include cotton and silk and pieces over 50 years old may also have beadwork in addition to shisha work. Motifs are varied, from very naturalistic animals to very stylized patterns and geometrics. Mismatched patchwork is also part of their charm. Museum collections have toran from the late 19th century, but most of the older pieces available on today's market are mid-20th century. Invariably, the vintage pieces have some damage - in my mind, patina - and there are also many newly made toran available as well, although the details and quality of the silks doesn't match that of the older pieces. The decorative possibilities, in particular for children's rooms, are obvious. They make charming valances or would be perfect fronting a bed canopy. Some toran are as long as 30 feet and I have seen them draping the edges of party tents as festive adornment.

IMAGE | Antique Kutch Rabari Banjara Toran via EthnicIndianArt

In modern-day interior decor, toran can be used in a quite literal context to embellish the threshold, as in this rituously joyful, over the top Indian themed space that was featured in Marie Claire Maison.

IMAGES | Bollywood Boudoir via Marie Claire Maison & Vintage Toran via IndianBeautifulArt.com

But they are also incredibly sweet when taken completely out of context and used in ways you might not expect like here, hanging over a kitchen nook in floral designer Nicolette Camille's Brooklyn apartment. This toran also defines and elevates what would normally be a rather simple kitchen.

IMAGE | Nicolette Camille's Brooklyn, NY home via Design*Sponge

Perhaps best of all is when toran are part of a truly global design aesthetic. In Maryam Montague's Marrakech master bedroom, featured in Elle Decor, this toran-like textile used as a window valence mixes happily with decorative items from many nations, including France, Mali, and Morocco.

IMAGE | Maryam Montague's Marrakech master bedroom via Elle Decor

Have you used a festive toran as decoration in your home, or do you have something else to share with us on this topic? If so, we'd love to hear all about it. Please leave a comment below or email us at info(at)clothandkind(dot)com.

ABOUT PROVENANCE | Provenance offers a scholarly nod to the history of iconic styles in textile & design and is guest edited by Jacqueline Wein of the blog Tokyo Jinja. Previous Provenance topics include: Kasuri & Kuba Cloth.

Provenance: Kasuri

The idea for this Provenance column has been in my mind for a couple of years, yet I've never quite had the wherewithal to make it happen in the substantive way in which I imagined it. For this reason, I am thrilled beyond words to have someone here now who is perfectly suited to pen this column because of her unique background as a design historian and also because of our shared appreciation for a global sense of style that often times comes from the use of age old techniques. Please welcome CLOTH & KIND's newest guest editor, Jacqueline Wein of the wonderful blog Tokyo Jinja. Jacqueline is an antiques dealer, design historian and “trailing spouse” living in Tokyo, Japan with her husband and two beautiful daughters. Tokyo Jinja (jinja means shrine in Japanese) tells the story of her travels throughout Asia and elsewhere looking at decorative and fine arts as well as chronicling her interior design projects. Always able to spot the proverbial needle in a haystack and sort the valuable from the junk, she combs Tokyo flea markets, better known as shrine sales, for treasures each week for clients around the world. Porcelains, textiles, woodblock prints, baskets, vintage fishing floats, and katagami stencils are just some of the finds that come her way. And there is nothing she likes better than imagining and researching an object’s past and finding a modern day use for it. She cut her teeth at the 26th Street flea markets in New York and Les Puces in Paris, and honed her Asian expertise along Hollywood Road in Hong Kong. Jacqueline's incomparable background makes her the most natural guest editor to author this column, which offers a scholarly nod to the history of iconic styles in textile & design. KRISTA

prov-e-nance \ˈpräv-nən(t)s, ˈprä-və-ˌnän(t)s\ noun. the place of origin or earliest known history of something.

Guest edited by Jacqueline Wein.

These days, ikat has become a household word, extending well beyond those in the textile world. Kasuri, on the other hand, is not, although it is the Japanese form of ikat, in which the weft and/or the warp threads are tie and resist dyed before being woven. That simply means that very tight binding threads are wrapped around all the places that are not meant to take the colored dye. Traditionally, kasuri was made from hand spun durable cotton using natural indigo and patterns were white against the blue, created by those areas left uncolored by the binding threads. Like many other indigo cottons, these were everyday fabrics worn by the common people. Aptly so, as indigo is credited with having the ability to strengthen fabric, making it more durable, as well as being able to repel bugs and insects which makes it ideal for the clothes of those working in the fields. Even as late as the early 1970s, most rural workers in Japan were wearing kasuri garments and Amy Katoh, author and owner of the iconic Blue & White store in Tokyo remembers the gardeners around the Imperial Palace wearing it through the 1960s.

Over time, additional pigments and modern designs were added to the mix. Occasionally, I stumble across an unusual two-tone piece that is not blue, like this madder colored one, although these tend to be more recent examples. But most kasuri still has an indigo base, even the modern machine-produced ones.

The complexity of the kasuri technique lies in having to plan where the pattern will go, not just before weaving, but as the thread itself is dyed. The charm of the technique lies in the slight blurring at the edges of the patterns and images, giving the fabric a soft sense of movement. Most ikat is designed with patterns laid out on the warp – the stationary threads on the loom – which is much easier to produce. Kasuri tends to be weft ikat, which allows the weaver more control in varying the piece as they go, but is also harder to plan and create. The paler wispy white areas in these examples are woven that way. Solid white areas in kasuri are actually double ikat, meaning they have patterns placed across both the warp and the weft, which is very technically demanding. Interestingly, while there is a tradition of ikat in almost all world cultures, only three countries - Japan, India and Indonesia - produce double ikat. Kurume kasuri, as shown below, is a regional geometric form that highlights this double ikat very well.

The areas of single and double kasuri are also easily distinguished from each other in the traditional length of fabric sourced by designer Maja Lithander Smith and I in Kyoto, which she had made into this beautiful bolster pillow. And I love the textile play with the more common Uzbek-style ikat on the pillow behind and the Japanese classic asa-no-ho (hemp pattern) on the vintage geisha pillow on the side table shelf.

Much kasuri is comprised of small repetitive geometric shapes, but it is also possible to create images and scenes with the technique. Pictorial kasuri is referred to as e-gasuri and the variety of patterns is endless - from literal patterns like this butterfly, to allegorical ones like this thunderstorm dragon pattern. Debate rages about where from and when ikat techniques were introduced to Japan, and some even believe it was invented independently at the end of the 18th century, but either way, this distinctive e-gasuri is Japan's own.

Kasuri is width limited by the narrow loom size prevalent here, being approximately 12-14 inches wide. Weaving was and is devoted to making kimono and other garments, which are constructed of vertical strips of cloth sewn together. A single tan, or bolt of cloth measures approximately 9-11 meters long as that is what is needed to construct a kimono. While it’s not unusual to visit antique markets and shrine sales in Japan with their racks of vintage kimono, it’s less common to come across great varieties of old kasuri ones, although I occasionally do. It’s eminently possible to take a kimono apart and re-use the fabric for other projects. Small vintage pieces perfect for modern day uses as pillows, table runners and accent fabrics are often found this way.

Larger items such as futon covers and furoshiki (wrapping cloths) were made by sewing strips of kasuri together. This early futon cover is made from hand-spun cotton and features both a realistic camelia and a stylized floral diamond called a hana bishi. It has aged and faded over time, adding to its charm and now displays beautifully as a throw over the back of a sofa.

Modern developments in weaving after WWII meant that yarn was no longer necessarily handspun and much of the dyeing process changed. Different kasuri stencil techniques emerged wherein the fabric was loosely woven first, stenciled with color and pattern, only to be tightly rewoven again. This sped up production and allowed for additional complexity in designs. Foreign influences and more varied coloration became common. Today, the word kasuri is often thrown around incorrectly referring to other kinds of Japanese textiles that use an ikat-like technique such as Meisen, Omeshi and Tsumugi silks, which were extremely popular from the art deco era through the post-war period. Their designs were the height of modernity at the time, and still feel extremely fresh today.

I am always hunting for vintage kasuri in good condition. If you are seeking Japanese textiles, including kasuri, shibori, katazome, tsutsugaki, silks, patchwork boro or anything else interesting please don't hesitate to reach out to me at jacquelinewein(at)yahoo(dot)com. And if you have any examples of kasuri in your home, please do share with us at info(at)clothandkind(dot)com.

Provenance: Kuba Cloth

prov-e-nance \ˈpräv-nən(t)s, ˈprä-və-ˌnän(t)s\noun. the place of origin or earliest known history of something.

ABOVE | Fabric Detail

Kuba Cloth is a rather magical kind of textile to me - it's organic and earthy, made in a primitive sort of a way, yet reads as quite modern when used just right in interior design. I've been drawn to it for a long time and have been collecting lovely vintage pieces that really strike my fancy whenever I stumble across them. Some I've used in my own home, like the one below, and others I'm saving for clients or to sell in CLOTH & KIND's online atelier which will be launching later this year (oh, if you'd like to be notified when the shop launches, please do sign up here).

ABOVE | My own vintage Kuba Cloth, mounted on nubby burlap and framed in a simple acrylic box, makes a total statement at the top of the stairs in my home.

Part of what makes ethnic textiles like Kuba Cloth so incredibly beautiful, at least to me, is knowing their history and understanding the time, technique, cultural significance and love that went into creating them. Is the same true for you? I hope so! It's because of this that I've created this new column. On a monthly basis Provenance will offer a scholarly nod to the history of iconic styles in textile & interior design. Since this is the first, please don't be shy about letting me know what you think and if you have any suggestions for styles you'd like to see covered in future Provenance posts.

ABOVE | Fabric Detail | Bedroom

ABOUT KUBA CLOTH Using the leaf of the raffia tree, the Kuba people of the Congo first hand cut, and then weave the strips of leaf to make pieces of fabric, often called raffia cloth. There are several different sub groups of the Kuba people and each group has different and unique ways to make the fabric - contributing to the wide variety of styles you'll find of this fabric. Some make it thicker, longer, shorter, or with different patches and/or colors. Each patch is symbolic and many times a piece has multiple meanings. When Kuba cloth originated it is thought that there were probably no patches used, but because the cloth is brittle it and tears easily, it's likely that the patches were used to repair the frequent tears. Later each patch developed a meaning and different patterns were uniquely arranged to tell a story. I love this... how the function ultimately became the form.

The process of making Kuba cloth is extremely time-consuming and may take several days to complete a simple piece. Both men and women contribute in equally important ways to the production of this fabric. First, the men first gather the leaves of the raffia tree and dye it using mud, indigo, or substances from the camwood tree. They then rub the raffia fibers in their hands to soften it and make it easier for weaving. After they've completed the base cloth the women set about embroidering it. They do this by pulling a few threads of the raffia fibers, inserting them into a needle running the needle through the cloth until the fibers show up on the opposite end. They use a knife and cut off the tops of the fibers, leaving only a little bit showing. Doing this hundreds and hundreds of times leads to the formation of a design. Kuba Cloth designs are seldom planned out ahead of time, and most of the embroidery is done by memory. In my opinion, this is part of what makes each imperfect piece so lovely and, clearly, so unique.

INCORPORATING KUBA CLOTH IN YOUR HOME Enchanted yet? There are so many ways that Kuba Cloth can be incorporated into interior spaces, and because of its dramatic design a single piece can make a major statement. Be sure to check out the shopping & inspiration resources below.

In addition to my own, I also wanted to share another Kuba Cloth wall hanging because I really, really love this as a way to showcase a long piece of this pretty fabric.

ABOVE | The Kuba Cloth above hangs in a long hallway of a gorgeous Streeterville condo in Chicago that belongs to a dear friend and former Condé Nast colleague of mine, Pam Dolby. It was placed by her talented designer Cindy Ilagan-Hengge, at the Kiran Design Group.

Admittedly, finding that one perfectly beautiful piece of vintage Kuba Cloth can be like searching for a needle in a haystack and the most stunning pieces are, not surprisingly, expensive. An alternative to finding an original piece of this fabric and transforming it for your space is to simply add a pillow or two. I've scoured the sources to share a few of my faves, some authentic Kuba Cloth and one awesome interpretation of it, complete with fun, shiny sequins, by Serena & Lily...

ABOVE | Mally Skok | Mark Alexander | Serena & Lily

Want to know more about Kuba Cloth and/or are you ready to shop? Check these out...

SOURCES | My Sources + More Information Africa Imports Kuba Textiles: An Introduction Wikipedia

SEE MORE | Kuba Cloth Pinterest Boards Inspired | Kuba ClothKuba ClothKuba Art Cloth

SHOP | Kuba Cloth Sources Africa and BeyondD. Bryant ArchieHaba Na Haba Hamill Tribal Textiles Kathleen TaylorL'Aviva Home Michael Donaldson AntiquesThe African Fabric ShopThe Loaded Trunk

Do you have a photo or story to share of how you've used Kuba Cloth in an interior space? Comment below and/or email it to info(at)clothandkind(dot)com and I'll post my favorites to my Kuba Cloth board on Pinterest, which will continue to grow and be an evolving resource for all things Kuba Cloth.

Provenance: Vintage Ikat Scarves

Understanding the provenance of an object always makes it that much more special. And so when I learned how these gorgeous vintage ikat scarves from L'Aviva Home came to be, I felt compelled to share the story of their journey with you.

As told by Laura Aviva of L'Aviva Home... I discovered that this vintage fabric existed when I was in Uzbekistan last year. I found pieces of it stashed under a worktable in a workshop in Samarkand, and fell completely in love. There's an incredible story to these pieces, as they encapsulate part of Uzbek/Central Asian history.

During Soviet times, home based crafts were banned in favor of factory production, but with an emphasis placed on top quality materials. And so the age-old Uzbek tradition of ikat was translated to the factory model. Instead of following the extensive, 37+ stage process involved in handmade ikat production, ikat designs were printed on swaths of meticulously produced silk crepe de chine. There were very stringent criteria imposed upon the production of this fabric, starting from the way that the cocoons were raised, and continuing through to the quality of the weave on the machines. And the result was this incredibly luxe, vibrant fabric. The factories were located in the Fergana Valley (the center of silk production for all of the Soviet Union/Soviet block countries). This region continues to be a major silk producing region, and is where present-day ikat is woven.

This fabric was highly coveted (and expensive, even in Soviet times). Brides purchased small swaths, all they could afford, enough to stash away in their dowry chests and then make a caftan or pants with (or both, if they were particularly flush) come their wedding day.

As the soviet-block countries began to gradually open during the late 80s, other fabrics made their way in, and new obsessions formed for viscose and other synthetic fabrics - something that the people had never before seen. As trends changed, the swaths of crepe de chine ikat often languished, forgotten, in dowry chests across the country.

We now have a virtual army of scouts throughout the Uzbekistan, gathering all of the fabric they can find for us. And, from it, we're fashioning these luxuriously large scarves (large enough to make super pareos/sarongs). And we're finishing them with contrasting-color zigzag stitching that emulates the stitch that was done during soviet times.

Each uniquely designed scarf is either one-of-a-kind or very limited edition and captures part of the story of Central Asia – of history, of memory, and of unyielding creativity. We are captivated by these forgotten treasures, and thrilled to add them to our collections at L'Aviva Home.