prov-e-nance \ˈpräv-nən(t)s, ˈprä-və-ˌnän(t)s\noun. the place of origin or earliest known history of something.

Guest edited by Jacqueline Wein, Tokyo Jinja

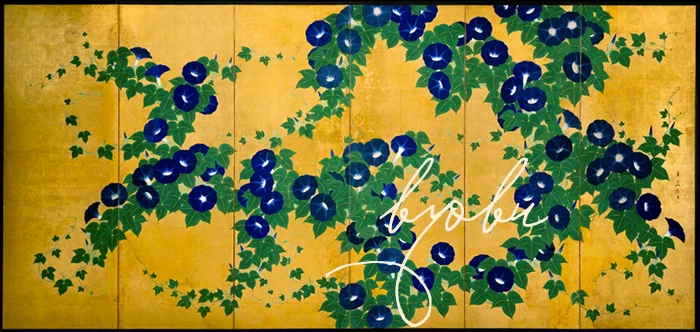

Perhaps the very essence of Japan can be found in the hand painted screens, called byobu, which have flourished as an art form in Japan since the 8th century. Byobu literally means “wind wall” which gives a clear sense of their original purpose – to block drafts. Over time, their mobility and flexibility allowed them to be used almost anywhere, to block unsightly objects or repurpose a room, as well as serving as beautiful backdrops for tea ceremony, ikebana and visiting dignitaries. Ornate screens and those using gold and silver leaf helped proclaim the status of their owner. Like much of Japanese artwork, screens originated in China but were slowly but surely domesticated and changed in Japan, with a high point being the introduction of paper hinges, allowing the artist a single large canvas to create an image, rather than completely divided panels.

I considered writing on other subjects this month, but with my imminent departure from Tokyo, I realized that I had to cover something very near and dear to my heart. Add to that my discovery, at a big antiques fair earlier this month, a divine silver leaf byobu painted with naturalistic pine in the richest of greens and my topic was set.

Of course this beauty came home with me where I cannot stop admiring the finesse of the painter who implied mountains in the background with the merest hint of line. The silver leaf literally seems to glow as if lit from within.

The period between the late 16th to the 17th century is considered the "golden age" of byobu painting, with daimyo and samurai leaders commissioning works of art on a large-scale, designed to decorate their castles and awe their constituents with their wealth and power. Screens from this period often continue to reflect a bold Chinese heritage and make free use of bold brushstrokes and Zen themes.

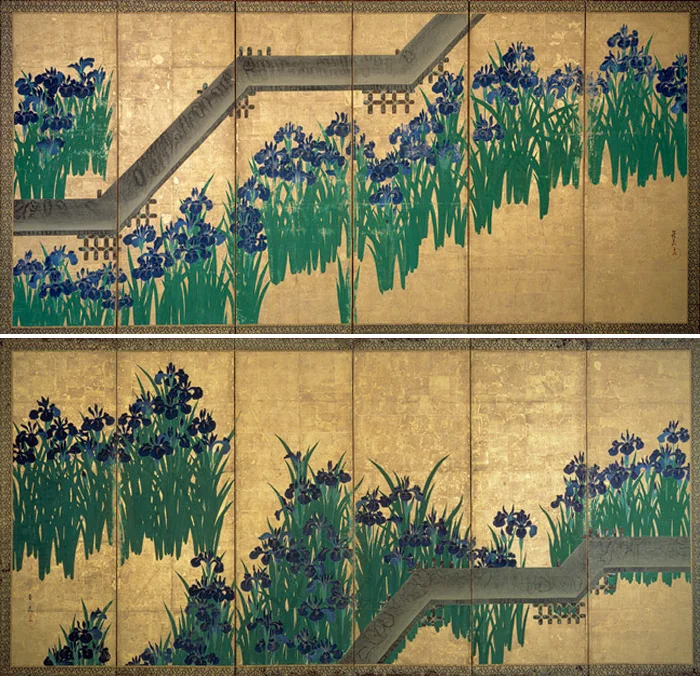

Prosperity under the Tokugawa shogunate from the early 17th century through the mid-19th century, encouraged painters of various schools to create screens in many different styles – not just for the samurai and aristocratic elites, but for wealthy farmers, artisans and merchants. The Kano school is perhaps the most well-known, being the dominant school style for nearly 400 years. The Kano family itself produced many great artists and many students of the school went on to take the Kano name. The Rinpa school, created in 17th century Kyoto, is one of the other most famous schools, known particularly for the work of brothers Ogata Korin and Ogata Kenzan. I have written about the Ogata Korin iris masterpieces before, and they continue to be some of my favorites.

Other schools include the Tosa school, whose subject matter and techniques derived from ancient Japanese art, as opposed to schools influenced by Chinese art, notably the Kano school. However, by the late 17th century divisions between schools had become less marked as the artists willingness to experiment broadened.

As the breadth of topics widened, so too did screen commissioning and ownership. Most common were pairs of full height 6 panel screens, but other shapes and sizes proliferated with specific names and uses. Topics such as the four seasons, flower studies and detailed works featuring the Tale of Genji and other stories were popular. I particularly enjoy some of the more casual screens showing everyday life - like this pair of tagasode screens - meaning "Whose Sleeves?" a common theme depicting beautiful kimonosdraped across a wooden rack. Generally unsigned, tagasode screens are thought to have been painted by local artists whose ready-made works were sold to buyers off the street, rather than being commissioned.

Today, screens are more likely to be hung on the wall rather than stood on the floor. They lose some of their visual movement that way, but it also enhances the viewers ability to encompass the painting directly. I love the parallel between the silver leaf grids in the screen and the Bennison fabric pattern in this room by Windsor Smith.

Finely detailed story screens like this 17th century byobu depicting the Genki Heike Battle between the Minamoto clan and the Taira clan may have had their heyday in that century, but feel just as relevant today when mixed with an antique Spanish refractory table and patchwork boro in Amy Katoh's riverfront home.

Their detail or simplicity, their ever-changing response to light, their functionality and portability and their ability to work in any style decor, make byobu any decorator's best friend. For more images and information about these Japanese beauties, you can visit my blog Tokyo Jinja and my Byobu Board on Pinterest.

Have you used byobu in your home or a client project? We'd love to hear about it.

IMAGE CREDITS | All byobu screens via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, other credits as noted and linked to in the post above.